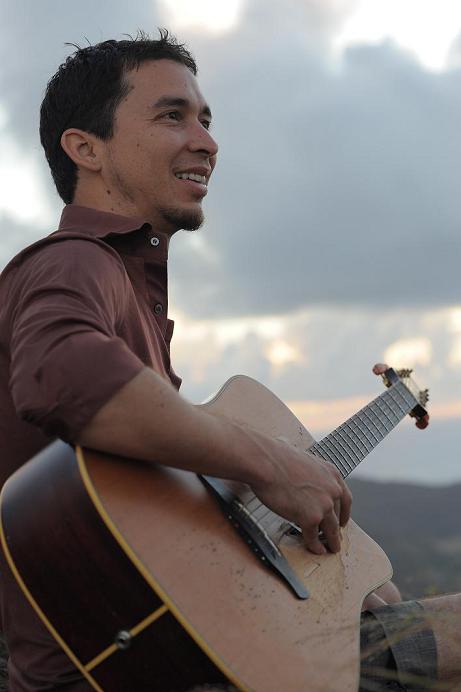

Interview: Makana

Some think that music has a mighty purpose. It does not exist just for our enjoyment, but can actually influence our opinion and truly change the world. Makana is a musician whose whole career has been founded on those philosophies. The Hawaiian slack-key guitarist’s lyrics are frequently focused on political issues and problems facing society. They perfectly depict his firm belief in writing about relevant subject matters.

In this conversation, Makana discusses his latest protest anthem inspired by Bernie Sanders, his involvement in the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the dangerous measures he takes when writing a song.

Laura Antonelli (Songfacts): What process results in the best outcome for you when writing a song?

Makana: I don’t have a system. It’s like growing a farm. Plants all behave differently. When I get inspired, I just feed at my energy, which is like water or sunlight. So they all grow at different paces. Some of them come up super fast. Some of them take years. Some of them require lots of research. Some of them don’t. So I’m spontaneous and organic with my process.

Songfacts: Social change and politics are topics that frequently inspire your music. Why do you feel so passionate about those subjects?

Makana: I care a lot about humanity. I’m empathic so I can feel other people’s pain. Art is a vehicle to convey anything effectively and powerfully because it effects people’s emotions. People tend to make decisions based on emotion, so I try to use my art to inspire emotions of empowerment and to also bring awareness to imbalances. What usually inspires me to write a song isn’t something that I feel is harmonious or perfect. It’s usually something that’s a problem or there’s suffering or some kind of tension. I want to help resolve that or bring light to it so other people can be inspired to do so, too.

Songfacts: “Fire Is Ours” is your latest politically infused song that’s in support of Bernie Sanders. Can you explain why his message resonates with you so much and how that one came to be?

Makana: Well, if you watch the video and listen to the song, it’s about Bernie but it’s also about much more. The music video, which of course is synced to the song and the lyrics, it focuses on how mainstream media corrupts itself and twists the public perception of our options. So it’s a big critique of it.

I’m not the kind of person that only blames the people at the top. I feel like the masses have a lot of power to make choices, but when the masses are influenced by mainstream media and mainstream media works to make them believe that they don’t have options or they’re disempowered or weak or they’re just consumers, then we get the status quo, which is destruction of the earth and disillusionment of the middle class and all these things that adversely affect people and the planet.

So the song addresses that warped process of media and then it says, “I really want to have someone represent me in this republic that represents me and not just money.”

Bernie represents a lot of the work I was doing when I was involved in Occupy Wall Street. These issues enter the public discourse and enter mainstream media when there’s momentum, but they don’t go away when there’s not. Bernie is like a meme – a representation of a lot of the values and issues that many people care about and are working to bring changes. So I think that Occupy brought the conversation up into the public sphere and then Bernie’s bringing it to the ballot. Whether or not he wins and becomes President doesn’t mean that the movement and the values are going to become irrelevant. They continue on with or without him.

Songfacts: And what was the process of actually writing it?

Makana: “Feel the Bern” was this colloquialism that got popular early on in his candidacy. It was a fine line to riff something that was being recycled a lot and make if fresh. I was swimming one day last year and the melody came up for the chorus [sings], “And I feel the burn,” and I was like, “Oh, that’s cool.” I wrote it on piano and went into my workspace and started just playing with the idea of what I would want in a public servant. The characteristics and the values I would want, and those were the choruses. And then integrity and all of these attributes that are important that we can see in Bernie Sanders.

With the verses, it was expressing the emotional disenfranchisement, especially of the Left, and of everyone who got so excited about Obama and his generic platform of hope and change that didn’t really result in any of that because of the corporatist-centrist democratic leanings – the bankers that funded him and Wall Street. So I was trying to express the frustration of the voter in the verses. The voter feeling disenfranchised and then in the pre-choruses, try to ramp up the energy and say, “I’m not going to take this anymore.” And then go into the choruses where it becomes more positive and it articulates and envisions the kind of leader that we would like to see.

Songfacts: You already mentioned Occupy Wall Street. You wrote “We Are The Many” about the movement. What do you remember about writing that anthem and why did you feel so strongly about that specific group?

Makana: Well, I had just been to Zuccotti Park where it was ground zero for that in October of 2011. I came home. I was just hanging out at my house and reading articles. I think the New York Times had this article that was titled, “The Movement Lacks a Melody.” The synopsis was that the author was basically postulating, and rightly so, that if this movement had happened in the ’60s, many of the big artists would be singing about it. But no one was really singing about it except for a few on the fringe. He postulated that it was possibly because artists today are just not engaged in these issues and don’t really care about them. The industry has changed and the whole zeitgeist of art and social engagement has changed, which it has, but it pissed me off. It was an insult to my generation. Like I said, there was a sound argument there, but I wanted to counter it. So right there I got my guitar and in three hours, I had written a song.

I grew up learning about banking and the economy and how it’s used to leverage society in a way that empowers a few and disempowers the masses. I understand that system so putting it into a song was natural for me. I get emotional about it. People write a lot of songs about love and breakups, but there was an artist from Africa, his name’s Thomas Mapfumo, and he says something to the effect of, “We have a responsibility as artists to sing about what is going on in the lives of the people.” I feel like it’s our responsibility to sing about things that are valid to people’s lives. Music shouldn’t just be an escape away from people’s lives. It should be relevant.

It could be said that I create political art, but I just like to say that I create relevant art. If it’s something in the headlines every day and no one’s writing about it in music, I think that’s weird.

Songfacts: And why do you think artists today aren’t as engaged in those issues?

Makana: Well, people are doing less psychedelic drugs and the whole culture has changed. A lot of things changed in the Reagan era. The baby boomers that were a big part of that movement bought into that American dream: the white picket fence and the mortgage and the two cars in the driveway and having three kids. It’s not bad in and of itself, but the vision shifted. Once that became the vision, look at how much things changed. People had access to cheap credit and things were different in that era. What the millennials face today is radically different than the options their parents had post-World War II or even their grandparents, so I think the economy is different. Technology has shifted things. Social habits have changed.

But also the music labels and the corporations co-opted a lot of the movement. We had this underground punk movement that really was anti-corporate culture in the ’80s. The corporations then realized, “Oh my God, there’s money here. There’s a market here that we’re not adapting.” So they just basically co-opted the punk market and that’s where you have this corporate punk. I don’t want to name names, but the sound of being loud and aggressive remained, but the message got neutralized and sanitized. It’s sad when you see music that gets gutted of its real meaning. It has all the sheen and pizzazz and maybe the beats and the loud guitars and the yelling or the emotions, but where’s the substance? I’m not saying across the board, I’m just saying there was a general movement away from lyrics of substance and relevance.

I love ’80s music. It brought more of a fantasy world and I love that stuff. I have this quote, “I think only ’80s music can save the world,” because it’s so positive. But then the ’90s was really about bitching and whining, and that beginning of feeling disenfranchised like, Wait a minute, this whole dream thing is working for someone else but it’s certainly not working for me. And then came Disney pop and all that stuff, so it’s a big question why did people shift away from singing about these things. The easy answer is it doesn’t pay. Songs at the top of the charts aren’t usually ones that are decrying the system. I mean, in the olden days like “Imagine” and stuff like that, it was different, but people’s values have shifted.

Songfacts: “Mars Declares” is a song from an earlier album, Different Game, which talks about the irony of war. What motivated you to write it and what’s the tale occurring in it?

Makana: It’s actually an interesting story. I was doing a lot of anti-war rallies right before the US invaded Iraq, I think it was March of 2003. I was against that, and, of course, history has proven it was a bad idea for numerous reasons. I remember I was walking through my neighborhood in Hawaii. I was just imagining this story of this family whose father is in the military and his reasoning for being in it is to protect his family and homeland. So he gets shipped off and he ends up accidentally murdering this boy who has his own family. He ends up facing the father of that boy and it all comes home the grand irony that he’s actually the threat.

I think there are three verses. I finished the second verse and the bridge and got stuck on the last verse. So I was just perusing around the web when I found this soldier’s blog. He had been in a platoon with another soldier who had lived the exact story that I was writing. It shocked me so I contacted this guy.

I finished the song. It inspired me because it was a true story. It was so tragic and emotional. Of course, it was devastating for everyone involved. It’s not a unique story. It’s happened so much in different forms. But I contacted the writer and shared the song with him. We had a nice exchange. So that’s the story of that song, which is unfortunately true.

Songfacts: What triggered you to write “Manic” from the album, Ripe?

Makana: A personal experience [laughs]. I remember it was New Year’s Eve 2011? Turning 2012 maybe? I can’t exactly remember. I had this wonderful idea that I was going to stay home and meditate. All of my friends and my girlfriend went out to party, but I was like, “It’s sacred time.” So it’s one in the morning and I’m sitting there checking my Twitter and Facebook, and everyone is raving. I have those tendencies to have super-massive mood swings. Sometimes I won’t eat enough. I get writing or working and my blood sugar levels go up and down. I’m hyper-sensitive to that so I just had this drop and I got super depressed really fast. Just little things trigger it. I felt left out and I just felt dark. It can come on for no logical reason. When it comes on, it feels like the end of the world. So I was already sitting at the piano and I quickly wrote that song.

A lot of people relate to it. My writing is honest. I like to write about things that don’t seem like normal song subjects but things that a lot of people can relate to, and I always write about things that I personally go through.

Songfacts: What’s the story happening in “Starry Eyes” from your new album, Music You Heard Tonight?

Makana: Oh, yeah. Good question. The version of “Starry Eyes” on that album is just acoustic, but I’m actually going to do a produced version.

So “Starry Eyes” is about how the entertainment industry fills children’s heads with distorted ideas of love. I think the end line sums up the whole song: “No one ever finds true love, they only let it through.” It’s the idea that we can be made whole by another person. We definitely can be incredibly profoundly affected, shaped, influenced and moved by another person, but we have to be responsible for our own wholeness.

It’s not a popular theme in mainstream entertainment whether it’s film, T.V., music, or rap. So much of the lyrics today are toxic. There are some incredibly conscious artists out there, but they’re the minority. So for all the violence and the dysfunction and domestic problems and suffering in relationships that people go through, I hold the music industry largely responsible. You have 10 year olds with their earbuds in pumping these lyrics that were probably written by some assholes in Nashville. They’re just trying to sell records. They don’t give a shit. They sell or license that to the label or they do a deal and they shop those to the artists like a factory.

Of course, it’s not everybody. I’m talking the big industry. But those lyrics are going for hours a day into minds that are easily influenced. They absolutely affect the world view and the self view. That’s what media does. There’s a whole science around it. You can’t just let the lyricists and the pop singers off the hook. When you hyper-sexualize children and you idolize this romanticized view of love, it sets people up for huge disappointments.

Songfacts: You’re also a renowned slack-key guitarist and your song, “Deep in an Ancient Hawaiian Forest,” was featured in the movie, The Descendants. What can you recall about writing that one?

Makana: I wrote that song years ago. I used to hike into the forest in Hawaii. I used to like to go there right at dusk when it was turning dark. I would just imagine what was it like before Captain Cook arrived and the foreigners. What was it like in ancient Hawaii? If you were there in the olden days in the 1600s or 1500s, what would that be like?

People’s idea of Hawaii is so stereotypical. [Sings theme-like music] They get off the plane and they get a lei. They go to the beach. There is that, but it does not summarize Hawaii. Hawaii is profound, super heavy, powerful, deeply spiritual and incredible from a natural perspective. It’s the most isolated landmass in the world. It’s amazing. So I wanted to create a song that had that mystical feeling of ancient times in Hawaii.

When the music supervisor [for the movie] was doing the music, the director, Alexander Payne, had said, “We really want to use just slack key for this.” It’s not a big genre. There’s a limited amount of music and everything in the slack-key genre is generally uplifting, happy and light. But there’s this scene in the movie where the wife of the main character dies. She had cancer and they paddle her ashes out. They needed something that conveyed the depth of that emotion. They said mine was the only song that could do that and it did it just the way they wanted. So it’s really cool for me because I had written that song so long ago.

Songfacts: And you developed your own style of guitar playing known as Slack Rock. Can you describe the evolution of your style and technique?

Makana: Well, Hawaiian slack-key guitar is a style that’s indigenous to Hawaii. It’s from the 1800s. It’s called that because they slack the strings to change the tuning. So it’s a chord and once the tuning is tuned to a chord, you don’t have to hold the chord anymore so your hands are freed up. You can play a lead and with the picking, then you’ll do bass, rhythm, and melody. What that all means is slack key guitar is a Hawaiian way of playing that makes one guitar sound like three guitars. So you’re actually accompanying yourself. You’re alternating bass, rhythm, and lead. It’s this symphonic, beautiful, resonant style. I have over 100 tunings. It’s generally major chords – happy, peaceful, and uplifting.

Slack Rock is a nickname for the music I do that’s more aggressive outside of that traditional style, which has blues, rock, bluegrass, and raga influences, but I use the techniques of slack key. So I might play Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd or my own blues, but I can still make it sound like three guitars because I’m using the foundational techniques of slack key. It doesn’t sound Hawaiian. It sounds more contemporary or bluesy rock.

Songfacts: Do you approach writing an instrumental song differently than a lyrical song and do you prefer writing one over the other?

Makana: [Long pause] Hmm. Yeah, very differently. I don’t know that I approach them, but my brain process is totally different. Writing an instrumental song is radically different than writing one with lyrics because when I start to do lyrics, it’s a whole other operation.

I don’t have a system, but I don’t prefer one over the other. I love it all. Music to me is a language of emotion, so I ask, Is this making me feel the emotion that I’m intending to convey? Did that change or did that melody or did that combination melody and lyric move me?

It’s a mystical process. It’s arguably my favorite activity in the world. I’ve gotten to the point with writing where I actually love having unfinished songs. I love it because it just feels like I’m confident I can finish it. Remember those books when you were a kid, there were these books called Choose Your Own Adventure? You choose your own ending, “If you want this ending, go to this page.” I loved those books so much and my songs are like them.

It’s funny, I think songs are important but when you get really deep into music, songs don’t matter anymore. The form of a song can sometimes be limiting. Sometimes you want to express something, but you’re like, “Shit, man. I already played it like that. I want to change it.” If it’s a song that people know, they generally want to hear it the same way, but songs can be a double-edged sword. They can become limiting. Most people who have hits hate their hits after a while because they have to play them 10 million times, so I try to avoid that [laughs].

Songfacts: That’s why a song is always evolving too, right? It’s never actually finished.

Makana: I think so. I mean, that’s how I feel. Part of what makes my songwriting so diverse because I write in so many different genres and subject materials is that I use and create new tunings all of the time. Every time I make a new tuning, my muscle memory is useless. I have to re-learn the guitar in that tuning so it forces me to be creative. My hands don’t always land on the same positions and that habit can actually adversely impact writing because when you’re a musician, your hands tend to settle in positions they’re familiar with, and that’s just how your muscles work. But when you change the tuning those positions are irrelevant. They sound weird. They don’t make sense. So you have to re-learn it and it forces you to learn new things. When you’re forced to learn new things, you discover new things, and that really influences my writing process.

Songfacts: Is there a song out of your whole discography that you wish would get more attention from people?

Makana: [Long pause] Definitely at this moment “Fire Is Ours.” Unfortunately, the campaign didn’t share it. I don’t know if it’s because I made the video too controversial or what [laughs]. But I never edit my art or dumb it down. I just do what I do.

I think “Manic” could inspire a lot of people. A lot of people struggle with that – millions of people.

Part of my whole life and career is perpetuating an unknown tradition, so there’s not a big audience for it yet. But I’ve dedicated most of my life to that and then the political stuff is more community service for me. So this year I’m going to start recording something that is meant to be more for a broader audience. Not in Hawaiian language or hyper-political. I think my songs will start to reach more people. I’ve never prioritized being a star or pursuing any of that. I’ve just purely been an artist. It’s reflected in my body of work because it’s all over the place.

Songfacts: What’s the biggest challenge you encounter when writing a song?

Makana: [Long pause] The biggest challenge is not how hard it is to write a song, it’s how it impacts my life and relationships. Most of my super-heavy shit I haven’t released yet. I have hundreds of songs that are unreleased and there’s some really profound, heavy stuff.

I have a demo of a song I put out on my album, 25. It’s called “Saboteur.” “Saboteur” is probably one of the best song’s I’ve ever written. It goes:

It’s all part of your show

I should have known

I had front row

I was wondering why we couldn’t fly

How hard I tried

So many times I remember us fighting about nothing at all

You’re addicted to pain and it drains me until I fall

Saboteur, baby, don’t you undermine me anymore

It goes on. When I was writing that song, as an example, I go into dark places. My ex-girlfriend, her father was murdered when she was three or four. I wrote a song about her life. She couldn’t even go there. I had to go there in order to dig it out. I write a lot about death. One of my fans, her son accidentally killed himself. He was making honey oil from marijuana and accidentally blew himself up. He breathed in when the gas exploded. It took him three days to die and his Mom was there the whole time. It was the most horrible tragedy. He had a wife and kids, and he’s dead now. I wrote a song called “Undressing Room” for him. It’s online on YouTube.

So I write about heavy shit and to write it, you have to use your imagination and become it. When I wrote “Undressing Room,” I went in my room for five days. I put myself emotionally in that space and cried, threw up, and went through horrible sadness and devastation. It’s not my own so I adopt those energies and I invite them in. If I’m in a relationship, which I’m not now, but when I have been, it’s terrifying for people around me. They don’t understand that when I write a song, the whole world stops for me and I become that song. Whatever that character in the song went through, I emotionally go through. When I’m done with it, I’m done. I would tell my girlfriend when we were together, “Look. I have this feeling I’m going to write a song so I’m going to be a mess for three days.” She would just bring me food. I would become a basket case, but then this amazing life-changing piece of art comes out.

So that’s the hardest thing by far. It’s hard for me to have a relationship because it scares people. She always felt worried I was going to kill myself or I would get so depressed. But I have a way of holding those heavy emotions in me without them becoming me, but it doesn’t look like that from the outside.

I don’t know if that makes sense? It’s dangerous. Art is my life, and that part is by far the hardest part. There’s nothing hard about writing a song. If it takes a long time, fine. But it can be devastating for people in my life because they don’t understand my process of making the art.

No Comment